Motivation

Helping young learners give and follow directions in English is both important and challenging. Direction-giving language is tightly connected to the places students live, the landmarks they recognize, and the ways people in their communities typically talk about space. For this reason, we set the following goal: to support upper-primary learners in developing the vocabulary and expressions needed to describe routes and locations in English in ways that feel meaningful and relevant to their own contexts.

There are two main reasons for focusing on this goal. First, expressions used for giving directions are highly context-dependent. Because they reference local geographic features, they vary by country, region, and even neighborhood. For example, directional expressions in Korean cities are often block-based, as many new towns are designed on a grid system similar to New York (e.g., “go forward three blocks”). In contrast, rural Korean expressions may reference natural landmarks such as mountains. Chinese directional language may require terms like “cross the bridge” or “go around the roundabout.” Everyday buildings and landmarks also differ across cultures, leading to further variation in how directions are given.

Second, mastering these expressions requires repetition, but 5th- and 6th-grade students often become bored with traditional drills. Based on our team members’ teaching experience, students frequently struggle to use this vocabulary and these structures spontaneously. Teachers typically use drill-based activities in which students form sentences with target words. While task repetition is known to support language development (Bygate, 2018; Kim & Tracy-Ventura, 2013), over-reliance on repetitive tasks can lower learners’ motivation (Pinter, 2019). To address this, teachers have incorporated more varied and engaging techniques such as games, songs, and stories (Chou, 2011).

In response to this background, our learning tool is designed to help students construct city maps and practice communicating their ideas clearly in English through a hands-on, multimodal experience. This project integrates tangible play, language learning, and creative mapping to help beginning-level English learners build confidence in vocabulary use and direction-giving.

We target two specific learning goals:

- Students will be able to recognize and understand common city elements in English.

- Students will be able to give and receive spatial directions in English with increasing accuracy.

The primary audience is 5th- and 6th-grade students in countries where English is not the first language.

The learning progression is as follows:

- Students first learn basic map-related vocabulary, including building names (e.g., school, bridge, theater), directional words (right, left, forward), and movement verbs (go, turn).

- Next, they reinforce their understanding by matching words to related pictures, supporting early recognition and comprehension.

- Finally, students use physical blocks and drawings to construct their own city maps. They freely choose starting and ending points and repeatedly practice describing routes to a destination, using the expressions they have learned to form complete sentences.

Students at this developmental and proficiency level benefit from visual support, repetition, embodied learning, and meaningful context. Through this sequence of activities, they will gradually become more comfortable with and fluent in using map-related vocabulary and expressions in English.

Related Work

Giving directions

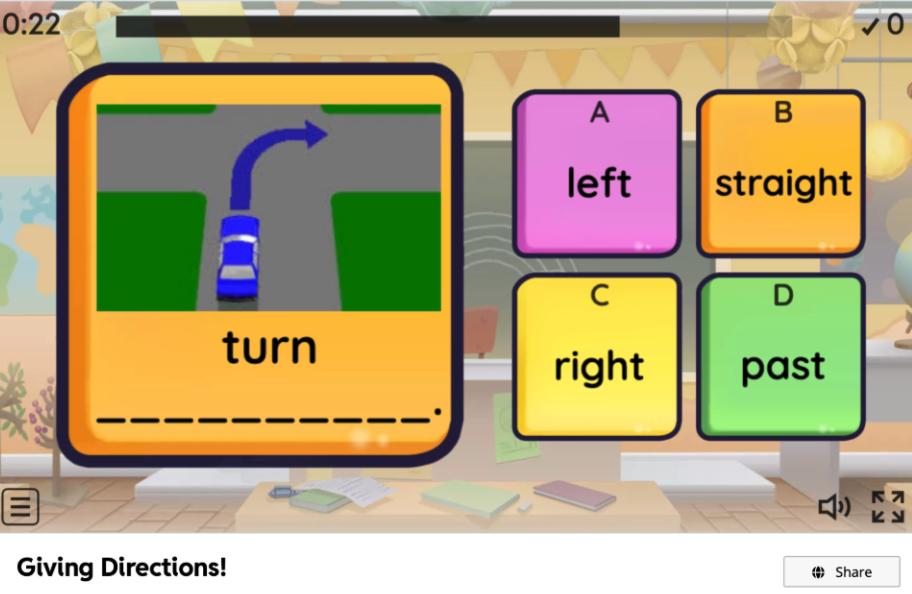

https://wordwall.net/resource/30165348/english/giving-directions

The directions game

https://www.elipublishing.com/p/thedirectionsgame?rc=eyJzZWFyY2giOiI5Nzg4ODUzNjQzNDM4In0%3D

We identified several existing learning materials that help students practice direction-related words and expressions, including flash-based “Giving Directions” games and card-based activities such as “The Directions Game.” These resources typically present pre-designed city layouts or fixed paths that students must follow, often in the form of drills (e.g., “go straight,” “turn left at the bank”). While such materials can support initial vocabulary exposure and controlled practice, they are limited in two key ways.

First, they offer little or no personalization. Learners cannot modify the map, add landmarks that reflect their own neighborhoods, or incorporate places they care about. As a result, direction-giving remains abstract and detached from their lived experiences with space and navigation. Second, these tools tend to rely on repetitive, closed-ended tasks. Students follow predetermined routes rather than generating their own, which constrains opportunities for creative language use and meaningful communication.

Our proposed solution builds on this work by retaining the structured focus on core direction-related vocabulary, but extending it into an open, learner-generated environment. Instead of navigating fixed maps, students construct their own city layouts with physical blocks and drawings, selecting starting and ending points that matter to them. This design directly addresses the personalization gap in existing materials: learners can embed familiar landmarks, experiment with multiple routes, and relate the English expressions to spaces they imagine or actually know. In doing so, our tool aims to bridge the strengths of existing direction-practice games (clear targets, repeated exposure) with a more flexible, multimodal, and personally meaningful learning experience.

Design Process

Prototype 1

Hardware |

Software |

|

|

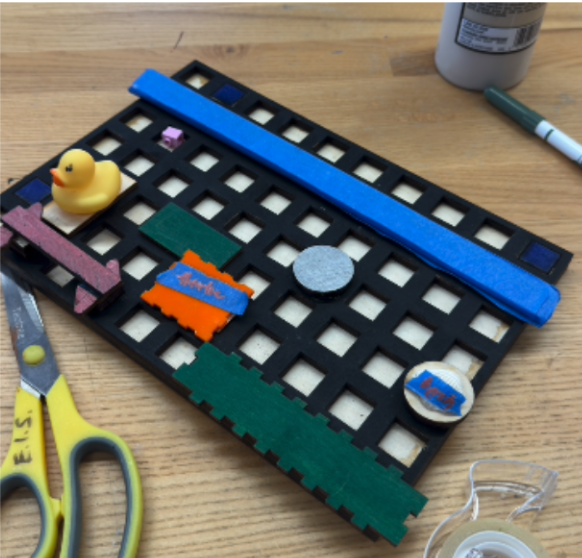

For the first hardware prototype, we differentiated the map elements by using different colors. We incorporated a mix of natural and arbitrary geographical features including a river, library, etc.

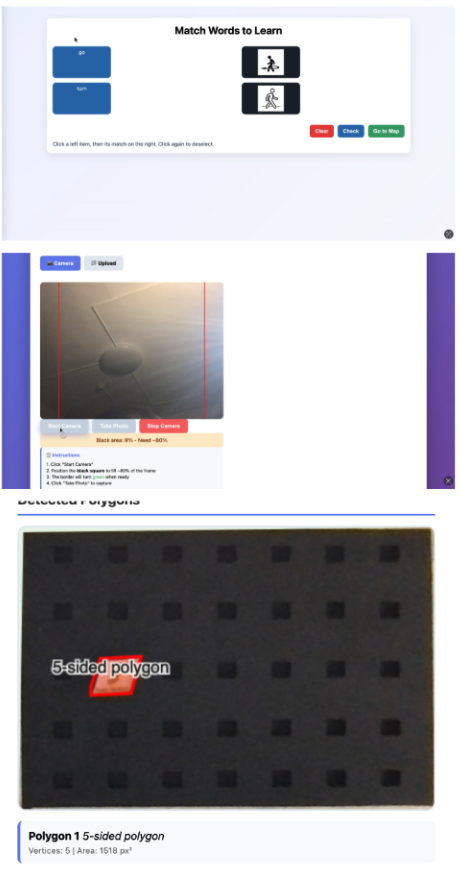

For the first software prototype, we chose Processing because it works well with images. Our idea was to let users take a picture of a physical map and then generate a 2D digital version of that map. Since the OpenCV library can recognize different polygons and shapes in an image, we planned to use it to distinguish different types of buildings. However, we soon found that the OpenCV library for Processing had very limited documentation, which made it difficult for us to implement our ideas.

User Test

We conducted user testing with graduate students who had experience teaching English as a second language. Although their English proficiency and demographics differed from those of our target learners, their expertise as educators made their feedback especially valuable. Pair testing was particularly effective, as it allowed us to observe how users interpreted the game and how understanding was co-constructed. In each pair, we first taught one participant how to (1) make a map, (2) set goals, and (3) explain how to get to a destination. That participant then taught the other how to play the game while we observed the entire process.

Through this user testing, we realized that the map design needed to be more concrete and explicit. First, we found that our wooden map required revision. Some users placed building pieces directly side by side, completely blocking the road, which made it difficult to see which paths were available. This led us to conclude that the roads should be wider and more visually salient. Second, we recognized the need to explicitly indicate orientation at the starting point, for example by having learners set a directional arrow to show which way the character is facing. Third, we realized that we needed a software component to help learners generate sentences using the target words. While we initially considered using physical cards, the limited number of cards constrained students’ thinking, and learners could only rely on the provided maps rather than creating their own.

Prototype 2

Hardware |

Software |

|

|

For the second hardware prototype, we reduced the size of the holes in order to create wider roads on the map. We also differentiated building types by varying the number of polygon sides (angles) for each type.

For the second software prototype, we experimented with several methods to provide auto-generated feedback on students’ route explanations. First, we attempted to use the OpenCV library to recognize different shapes on the map. However, even after repeatedly adjusting the threshold values, it was difficult to reliably detect the exact shapes we had created. Second, we explored using large multimodal models to analyze the routes via the Hugging Face API. This approach was not feasible in our context: the available laptops could not support multimodal AI models, and when we turned to cloud-based hosting services such as Databricks, we found that they supported only large language models, not multimodal ones. Given these constraints, we decided to limit the software to supporting sentence construction and to redesign the activities so that human facilitators or peers would provide feedback and check the accuracy of students’ responses.

Final Design

Hardware

Software

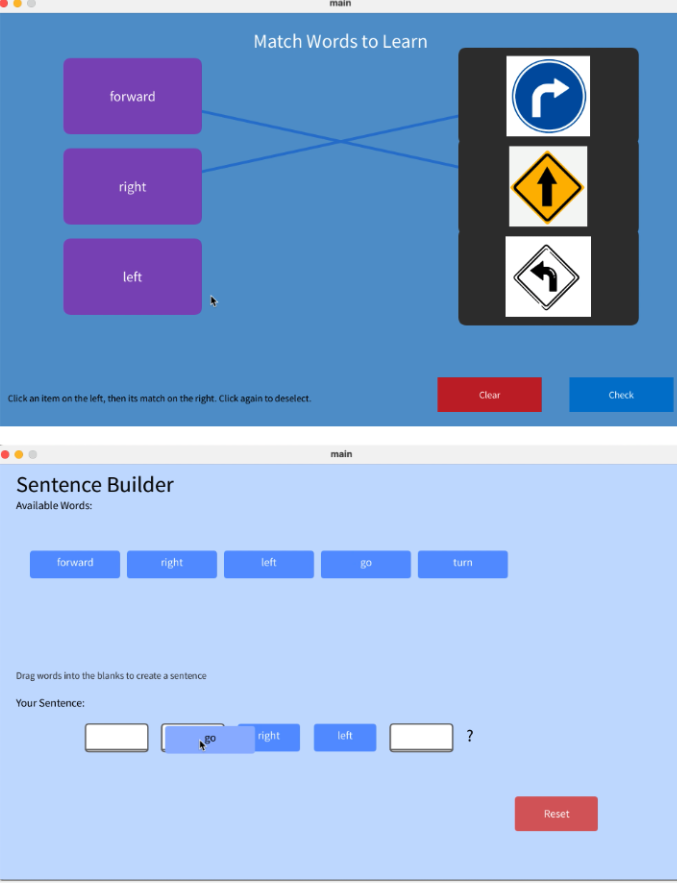

- Match

We added a star system so that students can see their learning progress. Students earn stars when they answer correctly. We also set the activities so that they can move on to the next task only after getting all the cards correct. This is intended to encourage more practice and ensure they fully learn the target expressions before advancing.

2. Make Sentences

We colored the blocks in different colors so that students can quickly find the words they need. We also added extra word blocks to help them form complete sentences. In addition, we attached an arrow to the starting marker so that students can clearly see which direction their route should begin.

Theoretical Rationale

Learning English vocabulary and expressions can often feel repetitive or disconnected from real-life communication. Our goal was to design a learning experience that is participatory, playful, and meaningful for beginning-level English learners. To do so, we drew on several pedagogical principles and relevant literature.

First, we build on embodied learning, in which students use physical action and manipulation to support meaning-making. By physically constructing the map and moving markers along routes, learners ground abstract directional language (“turn left,” “go forward”) in sensorimotor experience, which can strengthen retention and understanding.

Second, we emphasize authentic communication. Giving and receiving directions closely mirrors real-world tasks, positioning language as a tool to achieve a goal (navigating from point A to point B) rather than as isolated vocabulary practice. This focus on functional language use supports communicative competence and helps learners see the immediate relevance of the target expressions.

Third, we adopt a multimodal approach. Students work with visuals (maps, icons, colors), tactile materials (wooden pieces, blocks, markers), text (on-screen prompts, typed sentences), and, potentially, audio and storytelling. Engaging multiple modalities can deepen processing and provide multiple pathways for memory, which is particularly important for young learners and beginning language learners.

Finally, we foreground the student agency. Learners design their own maps, select landmarks, and choose their own routes and destinations. They generate their own directions on the computer rather than only repeating fixed patterns. This supports creativity, ownership, and motivation, while still allowing for repeated practice of core directional expressions.

This project is intended for use in classroom or small-group settings (e.g., 5th-6th grade EFL classes, after-school programs, or language labs) where students have access to both the physical map materials and a computer. In these contexts, the tool can be integrated into a lesson on map vocabulary and direction-giving, functioning as a culminating task that ties together embodied practice, communicative use, and reflection.

Technological Rationale

The design features and technological choices of our tool are closely aligned with these learning theories and goals.

The hardware components (wooden map, colored and polygonal building pieces, physical markers) directly support embodied and multimodal learning. They invite students to manipulate physical objects, arrange city layouts, and trace routes with their hands. Differentiating elements by color and shape makes spatial relationships and categories (e.g., types of buildings) visually salient, which supports comprehension and recall.

The software component complements this by providing a space for students to formalize their ideas in English. After constructing a route physically, students type (or in future iterations, speak) the directions into the computer. This bridges concrete, hands-on exploration with abstract language production, reinforcing the mapping between spatial concepts and linguistic forms. The tool can also scaffold sentence construction (e.g., through word banks or partially completed sentences), aligning with the goal of helping beginners gain confidence with key expressions.

Compared to a purely paper-based activity (e.g., a printed worksheet with a fixed map), our tool offers:

- Greater personalization: students design their own maps and routes rather than following a single pre-drawn layout.

- Richer embodiment: the tangible, reconfigurable hardware allows for repeated, playful rearrangement of space.

- Dynamic language practice: the software can guide sentence formation, log multiple attempts, and (in future versions) offer automated or semi-automated feedback.

Compared to typical computer-only direction games (e.g., static online maps with fixed paths), our tool:

- Embeds learning in tangible, collaborative activity rather than screen-only interaction.

- Gives learners more agency to create content (their own city and routes) rather than only responding to pre-designed scenarios.

- Better supports social learning, as peers or facilitators can gather around the shared physical map while students articulate directions through the software.

Overall, the integration of tangible hardware and supportive software is justified by our theoretical emphasis on embodied, multimodal, and communicative learning, and it provides clear advantages over both standard digital drills and traditional paper-based tasks.

Video Demo

Conclusions and Future Work

In this project, we aimed to solve the problem that students often learn direction-related expressions in English through repetitive drills that are not connected to their real lives. Existing games and worksheets usually use fixed maps that students cannot change.

Our tool offers a different approach. By letting students build their own city maps, choose their own routes, and then describe those routes in English, we connect vocabulary like “turn left” or “go straight” to a meaningful task. The combination of physical blocks and simple software supports embodied, multimodal, and communicative learning. In this way, our work points to how tangible, playful tools can make early language learning more engaging and relevant.

If we had another year to work on this project, we would:

- Add AI feedback: Use AI to automatically check students’ directions and give simple feedback on correctness and language use.

- Add a moving character: Show a character moving along the map each time a student completes a sentence, so they can immediately see whether their directions make sense.

- Add speech-to-text: Let students speak their directions and have the system recognize their speech, so they can practice both speaking and writing.

- Improve hardware and testing: Refine the physical pieces and test the tool more in real classrooms to see how teachers and students actually use it, and adjust the design based on their feedback.

Individual contribution

Lydia designed and built the hardware components, including the wooden map and physical elements, while I developed the software. Throughout the process, we regularly exchanged feedback on each other’s work. We collaboratively prepared and delivered the first and second presentations, and Lydia created the final presentation. I produced the demo video that is attached, and I also participated in the final exhibition.

Reference

Bygate, M. (2018). Introduction. In Bygate, M. (Ed.), Learning language through task repetition: Volume 11 (pp. 1–25). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Chou, M. H. (2014). Assessing English vocabulary and enhancing young English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners’ motivation through games, songs, and stories. Education 3-13, 42(3), 284–297.

Pinter, A. (2019). Agency and technology-mediated task repetition with young learners. Language Teaching for Young Learners 1(2), 139-160.

Kim, Y., & Tracy-Ventura, N. (2013). The role of task repetition in L2 performance development: What needs to be repeated during task-based interaction? System, 41, 829–840.

Appendices

- Slides: https://www.canva.com/design/DAG4CGmbPQc/ETzx8Y2QcD90sK1O4XAHgw/edit?utm_content=DAG4CGmbPQc&utm_campaign=designshare&utm_medium=link2&utm_source=sharebutton

- Video demonstration: https://www.canva.com/design/DAG7iLYtZNQ/n3ob7ZjoR494cpV--qXLEQ/watch?utm_content=DAG7iLYtZNQ&utm_campaign=designshare&utm_medium=link2&utm_source=uniquelinks&utlId=ha343fcd744

'STUDY > Ed.M.' 카테고리의 다른 글

| Fall 2025 수강 후기 (2) | 2026.01.20 |

|---|---|

| [T519] Processing Track (1) : Forest of Memory (0) | 2025.10.31 |

| [T519] Learning Toolkit Analysis - Chibi Lights (0) | 2025.10.25 |

| [T519] Dream Toy Project(4): Final (0) | 2025.10.24 |

| [T519] Dream Toy Project(3): Developing prototypes (0) | 2025.10.13 |

댓글